Union on Edge

/Home Nation flags of the United Kingdom.

(Image Credit: Setanta747 via Wikimedia Commons cc)

In light of the recent row over fox hunting, there appears to be bubbling angst in England with regard to Scotland and its place in the United Kingdom, and they are not good for future of the country.

Just before the SNP’s decision to have its 56 MP’s vote on the fox hunting legislation which only affects England and Wales (and breaking the party’s “principled” stance on not voting on such issues unless they were related to Scotland),Leo McKinstry of The Express was fuming over the prospect of Scottish First Minister and SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon “bossing England” with her insistence on having a say in the crafting of English Votes for English Laws (EVEL) – a process which would see English (or English and Welsh) MP’s having a greater say, if not outright veto, on bills going through the British Parliament at Westminster that are applicable only to England (or England and Wales).

He went on to claim that because of devolution, “English people are treated as second-class citizens in their own country” because Scottish MP’s still retain full voting rights at Westminster, resulting in a “gross constitutional injustice” (the West Lothian Question) in which Scottish MP’s have a say on all matters south of the Tweed, while MP’s from England and Wales have no reciprocating influence on matters that have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood.

McKinstry also banged on about the “huge funds that English taxpayers have to provide for Scotland”, and believes that Home Rule ought to be given to Scotland, along with Full Fiscal Autonomy (FFA), and that England should have its own Parliament in the spirit of the Scottish Constitutional Convention’s declaration of “the sovereign right of the Scottish people to determine the form of Government best suited to their needs.”

On Sunday after David Cameron withdrew the government’s fox hunting legislation that appeared doomed to failure with the SNP’s announcement of voting against it, Simon Heffer wrote for The Telegraph in terms that were similar to McKinstry last week.

He spoke of a “Scots insurgency” that if not stopped, would result is rising anger and resentment amongst the English, and believes that the original government plans for EVEL were too weak against the “insurgency” because while English MP’s can block amendments during the committee stage, MP’s from throughout the whole UK can vote on the final bill. This, he claims, “amounts to denying the English (and in some cases the Welsh) people democratic rights now enjoyed, at their expense, by the Scots”, with their “quasi-imperial right to interfere as they wish in English affairs while excluding English MPs from theirs.”

Further, he wants to see a “federal parliament” in which the whole House of Commons sits and decides on issues that affect the whole UK – which he described as “defence policy, foreign policy, security policy, the national lottery, and possibly some parts of the Budget (depending on the extent to which fiscal policy is devolved to the Edinburgh parliament).” However, where issues have been devolved to the representative institutions in Edinburgh, Belfast, and Cardiff, they ought to be decided at Westminster only by the MP’s whose constituents are affected. This, he believes, will mean that “the English question is decisively solved, and the Scots are put on an even footing with everyone else.”

Both of these opinion articles by McKinstry and Heffer are expressions of frustration by what they as an aggressive Scottish nationalism that is trying to break up the UK, but now has 56 MP’s in the Commons and is trying to “interfere” in the running of Britain, and in particular, England. The fox hunting issue as become just the most recent and highest profile case of the SNP making its mark known throughout the UK, and it has not – at least so far – gone down well with many voters in the rest of the UK.

These frustrations are understandable, but I am concerned that these views may be indicative of a rise in English nationalism in response to the rise of the SNP and what some people see as the near-constant whining and complaining that seems to have enveloped vast swaths of Scotland, resulting in a culture of grievance and resentment against the rest of the UK and blaming it for Scotland’s problems.

It is particularly concerning how Scots are increasingly being viewed as though they are foreigners in their own country – the United Kingdom. Simon Heffer’s use of the term “Scots insurgency” is an indication of this, for it appears to describe all Scots as though they are an alien force imposing their will on the rest of the UK. Perhaps he meant to say “SNP insurgency”, and if so, that would have been a more accurate term to describe the situation. However, the fact that he did not use that term speaks to the erroneous conflation of the SNP and Scotland, as if the two are one and the same, when in fact, they are not (though the SNP like perpetuating this myth).

These days, there are times whenever I hear or see someone use the term “the Scots”, and it is becoming unfortunately synonymous with the SNP (both north and south of the Tweed) and used in a way almost as if to say that Scots are a problem – a troublesome annoyance who need to be dealt with, and this is reflected in Heffer’s piece, when he said of “the Scots”:

“They have also voted for a Nationalist government committed to separatism. They managed not to win the argument last September, and so remain part of the Union. However, they have chosen to conduct their membership of the Union by means of aggression and constitutional offensiveness, like the bullies they were during the referendum campaign, and like the sore losers they have been ever since.”

At some level, it is not clear if and where he is making a distinction between all Scots and the SNP, but it certainly comes off as describing all Scots as having “chosen to conduct their membership of the Union by means of aggression and constitutional offensiveness.”

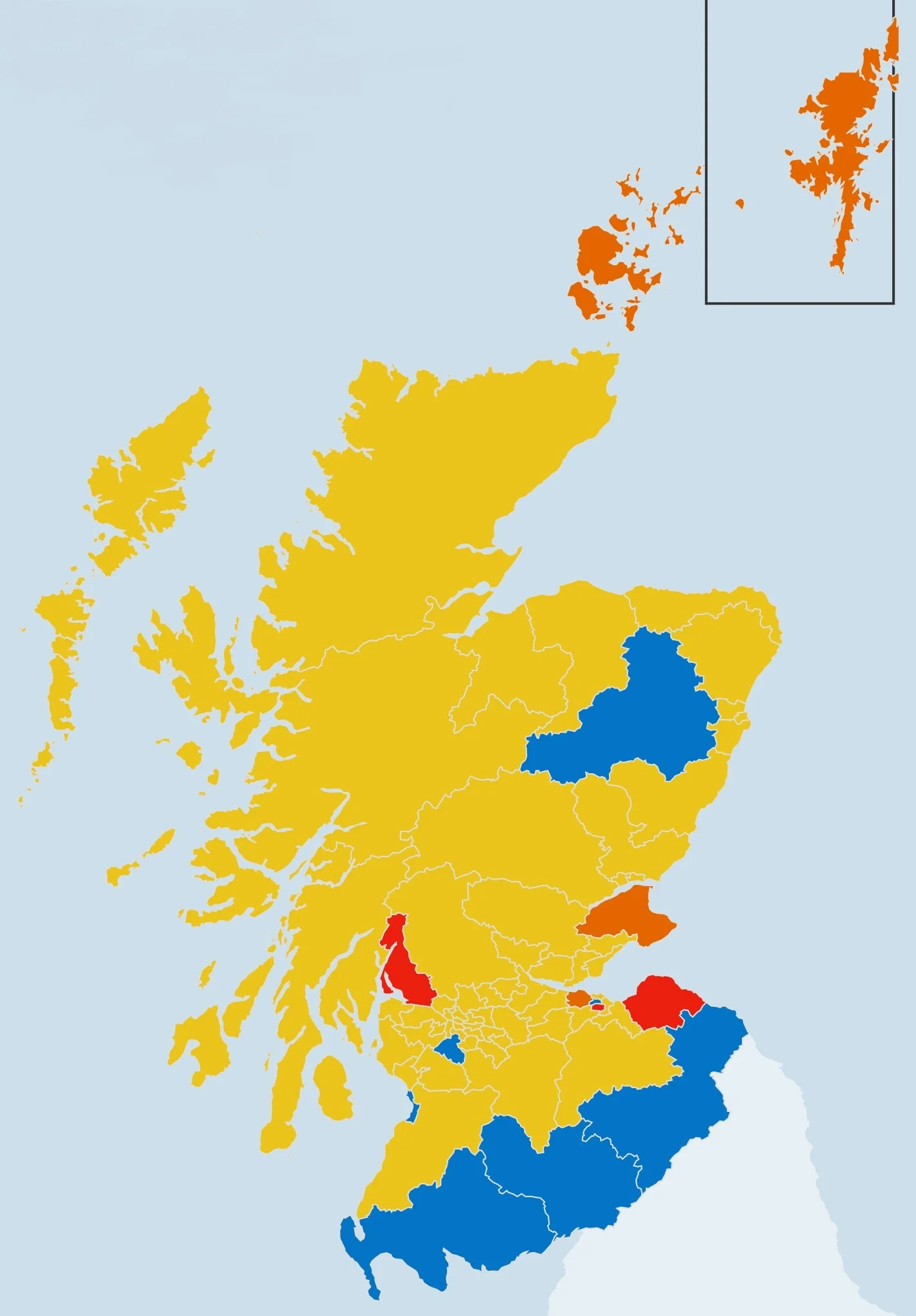

However, the fact remains that despite the SNP winning 56 out of 59 Scottish seats in the Commons, half of Scotland did not vote for it (which makes a case for some sort of proportional representation), and there are many Scots who are just as fed up with the SNP and their antics as people in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Not all Scots approve of the SNP and their separatist agenda, and just wish that the SNP would stop with the constitutional obsessions, saber-rattling, and constant displays of grievance, while there are real issues in Scotland that need addressing, which the SNP can do something about (without banging on for more powers).

Nevertheless, there are some voices that believe having Scots being full participants of parliamentary processes is tantamount to some form undemocratic tyranny, or in McKinstry’s words, a “gross constitutional injustice” which allows for Nicola Sturgeon to claim a “self-appointed role of trying to dictate how Britain (and particularly England) should be governed.”

Such emotive language is almost in line with the language used by some people in Scotland to argue for devolution in the 1990's and separation in 2014, with the talk of “democratic deficits” and the English imposing their will on Scotland, with laws passed by the British Parliament with a majority of English MP’s, though not Scottish MP’s, who have – as always since the beginning of the Union – full parliamentary representation like everyone else.

All this talk of whether English MP’s voted for this, or Scottish MP’s voted for that is irrelevant to the fact that the Palace of Westminster houses the British Parliament, the representative body of all of the people throughout the United Kingdom from Shetland to Land’s End, and whatever is decided by those MP’s is the result of elections by the people throughout the land, and – quite often – the votes break down based on party affiliation, and not on the basis of which part of the UK from which the MP’s came.

Devolution created an imbalance, but pushing for EVEL creates another imbalance at the heart of British governance by which the MP’s from certain parts of the UK are excluded from some parliamentary processes and votes simply because of their location.

Yes, there needs to be solution to the West Lothian Question, but there needs to be another way than EVEL. A person who truly believes in the Union – the very concept of Britain, and doesn’t view it in purely transactional terms – would strain every sinew to find and promote a solution to the West Lothian Question without resorting to the crudity of the short-term political – not long-term constitutional – solution of EVEL and telling non-English MP’s when they can and cannot participate in the parliamentary processes and votes at Westminster.

A more coherent and proper solution will be to create new legislative institutions in England, just as has been done in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales.

There could be a separate English Parliament, but there is a legitimate concern that it would rival the UK Parliament and that an English First Minister would be as powerful, if not more powerful than a British Prime Minister. Such an arraignment would prove detrimental to the foundations of the Union, whose whole point was to bring the peoples of Britain together into one country – a stronger one which would allow for the merging and sharing of resources, talents, and energies for the benefit and general welfare of all.

This is why there must be an end to the ad hoc political processes that have brought us to this point, and it is time instead for a constitutional convention for all of the United Kingdom, in order to forge a lasting settlement that everyone can find acceptable, if not entirely satisfactory – in the tradition of the signers of the US Constitution in 1787, all of whom were not 100% happy with the document they had created during the heated constitutional convention that year, but nevertheless came to the conclusion that they could not come to an agreement on something better.

Such a process, I hope, will retain Westminster as the sovereign body that is representative of the people throughout the entire UK at all times, while confirming or creating new bodies that take on powers similar to those of US or Australian states, Canadian provinces, or the German Länder.

The outcome would mean that Westminster becomes a true representative federal parliament in an overall federal system, unlike the bastardized form of federalism (EVEL) which was called for by Simon Heffer, with Scottish MP’s active for some things at Westminster, but not others (which is just as bad as the bastardized federalism advocated by some people in the SNP and their supporters).

Indeed, it appears that some people want easy short-term political answers, rather than hard long-term constitutional solutions befitting the complex nature of the UK. The honest truth is that at this point, there are no easy answers, but a convention where a diverse range of views can lead to a solution to the issues of British governance (including the West Lothian Question) is preferable to just about everything else.

The United Kingdom does need constitutional convulsions, and have one thing one day, and another thing the next. Piecemeal constitutional tinkering must be replaced by a singular effort to establish a reformed constitutional order (out of the chaos and passions of recent years) that is beneficial to all.

And if the SNP really wants to foster better relations with the people of the rest of the United Kingdom – as they claim they wish to do by focusing on affairs south of the Tweed – it would participate at such a convention and have the interests of the rest of the UK in mind while also being focused on Scotland, as opposed to the saber-rattling and complaining which will only hasten the introduction of EVEL.

But despite their protestations about EVEL (which a new study says will be detrimental to Scotland), some will actually welcome it, since they can complain about Westminster treating Scottish MP’s as second-class citizens. They would certainly like to portray it that way, and this will probably give Nicola Sturgeon the “material change” necessary to call for another referendum.

The issue therefore, is not about Scots, but about the SNP, and instead of biting on the SNP’s bait and dropping the nuke that is EVEL, people such as Heffer, McKinstry, and several others should call for convention in the hope settling these constitutional matters.

But aside from that, there needs to be a better and more fundamental understanding between everyone throughout the UK. Eye-grabbing headlines and emotive articles from some newspapers, as well as inflammatory speeches and comments don’t help the cause of the Union; rather, they inflame and harden attitudes against it by pitting the people of Britain against each other, such as referring to Scots as “subsidy junkies” and England being portrayed as land of greedy neo-liberal (Thatcher-loving) sociopaths.

To be quite frank, there needs to be a cooling down of emotions and rhetoric, and with the end of the referendum, I believed that this would happen. Unfortunately, this did not occur, and it sometimes feel as though one errant, insensitive, or ill-thought out comment or action will blow up the Union and end Britain as we know it. (Indeed, when writing my blog posts, I feel as though I have to keep various sensitivities in mind.)

Instead of coming to the inaccurate conclusion that Scots may have had a change of heart since last September, and dismissing the SNP and its 56 MP’s as a Scottish problem that neither the “English or the Government should be cowed by” as Simon Heffer says, columnists, journalists, politicians, and ordinary people from throughout the UK should actually get out and spend time in Scotland – perhaps on and off for several weeks or months, if not longer.

They should go to the leafy areas of East Lothian and Renfrewshire, as well as the housing estates in Glasgow and Dundee. Spend time in the Borders and Highlands, as well as the island communities. They should not see Scots as an alien and foreign people, but as their fellow British citizens who have many of the same concerns, fears, anxieties, and aspirations as they do. The problems that they face are the same ones faced by people throughout the UK as a whole, and it would be productive to actually meet with them in their homes and communities, and get to understand and know them better – beyond the preconceived notions and unhelpful stereotypes perpetuated by some corners of the media.

David Cameron, as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, in particular needs to spend more time in the country of his ancestry, as well as the new Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron and whoever will emerge from the Labour leadership election to replace Ed Miliband.

They should not go up there for one-day stops to “show the flag”, but stay there for days at a time, and become more engaged and focused on what’s going in Scotland, especially with regard to matters that affect the UK as a whole. They should hold meetings in Scotland, and find that there are still volumes of Scots who are supportive of the Union, who do not want to feel like foreigners, and who will appreciate the reaching out by their fellow British citizens from the Prime Minister on down.

Such people – some of whom are my friends – are trying cope with a deeply divided society, and they need support, especially from their fellow Brits. They want their voices to be heard above and apart from the SNP noise machine, and do not wish to be viewed as troublesome and annoying nuisances, but as beloved countrymen and women.

But of course, reaching out to those who voted Yes in 2014 and the SNP in 2015 will also be instrumental attempting to lowering the political temperature and smoothing relations throughout the UK and Scotland itself. David Cameron in particular may not be particularly liked in Scotland, but him being there for extended periods of time, meeting people, immersing himself into life up there (and possibly take some heat) – whilst still attending to his duties as Prime Minister – will at least be respected by many Scots.

Meanwhile, the SNP plans on getting out more into the rest of UK and expanding their scope to matters in places such as Leeds and Manchester, in the hope of championing for – among other things – increased transport links between Scotland and the North of England, as well as increased economic investment, which will be beneficial to Scotland. If this is what they intend to do, it is indeed high time for UK political leaders to spend more time up in Scotland for similar reasons of outreach and fostering better relations.

This outreach in both directions may even have the effect of fostering better feelings toward maintaining the Union, and rediscovering a common sense of Britishness. This may not be what the SNP wants, but it is certainly a possibility if they are good on their word of taking a more keen interest in matters that affect their fellow citizens in the UK outside of Scotland, which will require them to climb down a bit from their sanctimonious rhetoric about “standing up for Scotland” – as if to say that generations of MP’s from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Conservatives didn’t do so, while also working with their colleagues in the rest of the UK and not working toward dissolving the Union.

Indeed, there is a conceit about the SNP – a smugness, self-satisfaction, and arrogance that uses emotion and a sense of moral superiority that is used in elections and the recent referendum to beat down its opponents, especially pro-Union ones. That conceit has become more apparent following the row over fox hunting, and even some pro-SNP figures are starting to realize it as the party preaches from a moral high ground without actually following up with substantial action – especially at Holyrood, where the SNP has held the reins of government for eight years, and there are real substantive issues on health, education, and policing which need urgent addressing.

And for all of their preaching on social justice, they are certainly not taking or proposing the sort of radical action (i.e., substantial tax increases) that could scare off the middle class voters that the SNP – like all other parties – needs for victory. In the end, the only real aim they have is independence.

Will they really be willing to put their money where their mouth is, and actually constructively engage with people in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland – knowing full well that this may prove beneficial to the existence of the Union? Only time will tell. Perhaps greater cross-border interactions and mixing people up throughout the UK to break down preconceived notions about one another can lead to a better and greater understanding between them.

If nothing else, the rhetoric being used in the current political discourse – with talk of “insurgencies”, “junkies”, and “injustices” – needs to be toned down for everyone's sake.