Holyrood 2016: A Turning Point?

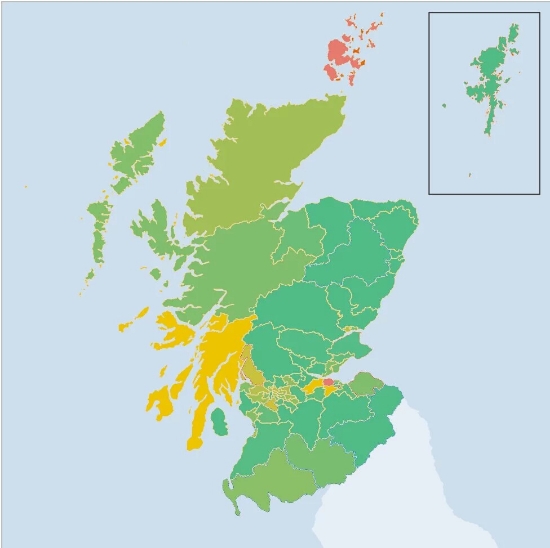

/2016 Holyrood election Map, with detail of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Image Source: BBC

Last Thurday’s Scottish Parliament election was one to remember for the fact that it turned out to be more interesting than projected. The seemingly unassailable SNP did win an unprecedented third term in power, but lost its vaunted majority from 2011 and found itself in the position of being in a minority government once again. Meanwhile, somewhat like Leicester City’s improbable victory of the Premier League championship, it was an evening of the three main pro-Union parties defying the odds and the going against the dire projections in store for them.

The Liberal Democrats set the tone for the evening by not merely retaining the Orkney Islands, but having Liam McArthur winning it with a vastly increased majority. Here, the SNP vote share went down by 0.8% from 2011, while the LibDem’s managed a massive 31.6% increase to end up with 67.4% of the vote against the SNP’s 24.3% and majority of 4,534 votes. To the north in the Shetland Islands, the party again increased its majority to send former Scottish LibDem leader Tavish Scott back to Holyrood for a fourth term, and though the SNP managed to increase their vote share here, the Liberal Democrats increased it further to take home the same share as they done in Orkney.

What was significant here is that Orkney and Shetland are represented as a single constituency at the UK Parliament and save for a fifteen year period from 1935 to 1950, have been sending Liberal and Liberal Democrat MP’s continuously since 1837, with the streak since 1950 being the longest run within any British parliamentary constituency and making it the safest seat for the LibDems.

For Scottish parliamentary purposes, the islands were split into two constituencies which have elected Liberal Democrats since their creation in 1999, and these became the last LibDem bastions in Scotland after the near wipeout of 2011 when they lost all of their mainland constituencies to the SNP, partly in response to their role as coalition partners with the Conservatives at Westminster. At the 2015 UK general election, then-Secretary of State for Scotland Alistair Carmichael held on to Orkney and Shetland with a reduced majority during the SNP landslide as he became the last Liberal Democrat MP in Scotland.

After holding on to his seat, Carmichael faced an attempt to have him removed from office by four constituents in Orkney over the “Frenchgate” memo controversy during the general election when he stated that as Scottish Secretary in the coalition government of David Cameron, he knew nothing of a leaked memo which said that Nicola Sturgeon told the French ambassador that she actually preferred Cameron as prime minister as opposed to then-Labour leader Ed Miliband. When it turned out that Carmichael was involved in the leak and he admitted to it, the “Orkney four” lodged a petition for his removal and force a by-election. Carmichael was eventually found not to have committed an “illegal act” and he kept his seat, but there seemed to have been untold damage to his reputation and the electoral chances of his party in Orkney and Shetland.

At least one of the constituencies (typically Orkney) had been projected as among those vulnerable to the SNP, but it seemed that the voters may have been turned off by what many people believed was a political witch-hunt to force out the last Scottish LibDem MP. In addition, there were no independent candidates in the running as there were in 2011 in both seats, and so the party romped home victories to keep them in the fold.

However, if those victories could have been written off as Orkney and Shetland being Orkney and Shetland – voting for LibDems no matter what, the same could not be exactly said about the two big surprises for the party down south. In North East Fife, it pulled off an upset by electing Scottish party leader Willie Rennie with a majority of 3,465 – gaining it from the SNP and effectively turning around last year’s result at the UK general election where a similar seat long-held by former UK LibDem leader Sir Menzies Campbell was picked off by the advancing Nationalists.

Further down in Edinburgh Western, the party regained this seat from the SNP with a majority of 2,960 votes under Alex Cole-Hamilton, and this again was a reversal of last year’s result when the seat roughly contiguous to it at Westminster (Edinburgh West) fell to the SNP in the form of the now independent (and troubled) MP Michelle Thomson, who was suspended from the SNP last summer over dubious real estate and property dealings.

In the end, the Liberal Democrats ended up with five seats in total with the inclusion of one regional list MSP from the North East, and so they have the same number of MSP’s from 2011, but keeping Orkney and Shetland, as well as gaining North East Fife and Edinburgh Western – fulfilling the pledge made by Rennie that he’d win seats from the SNP – was a victory and morale booster for a party that had been all but written off in Scotland.

As for the Tories, they exceeded virtually everyone’s expectations in a big way. Sure, they had been rising in the polls and some projections showed them retaining their existing seats and perhaps gaining Eastwood, Dumfriesshire, and Edinburgh Pentlands. But it was still inconceivable that the Conservative Party – so often labeled as “toxic” in Scotland since being wiped out in 1997 – would make anything but modest gains and come in second place.

Indeed, at the beginning of election day, the Tories themselves – at least privately and confidentially – were tamping down expectations and braced for the possibility of actually losing seats to the SNP. Then as the night progressed and the results flowed in, it became clear that the Tories were doing not just doing well, but very well, especially in areas where they had been the dominant party as recently as two decades ago and still have pockets of support at the local level.

Their first victory of the night came in Eastwood, just to the southwest of Glasgow. This result was significant because Eastwood was once the safest Tory seat in Scotland at Westminster until Labour’s Jim Murphy won it in 1997 and Ken MacIntosh had held the seat at Holyrood for Labour since the first devolved election in 1999. Last year, Murphy lost the UK parliamentary seat – now known as East Renfrewshire – to the SNP and the Scottish parliamentary seat became a three-way marginal between Labour, the SNP, and the Conservatives. As such, it was one of the most-watched races this year, and in the end, Eastwood reverted back to Tories under longtime regional MSP Jackson Carlaw with a majority of 1,611.

The changes in support for the Conservatives from 2011 to this year's election. Greener areas indicateincreases in support; redder areas indicate decreases in support. Almost all Constituencies had an increase in Tory Support, especially in the Northeast and Tayside against the SNP. Image Credit: BBC; Graphics modificationand overlay by Stephen McGroarty

Then the Tories managed to hold on to Ayr along the west coast under John Scott with a reduced majority of 750 between him the SNP candidate. To the southeast along the border with England, they won another three-way contest by capturing Dumfriesshire from Labour’s Elaine Murray, who had been the constituency MSP since first standing for it in 1999. This area forms part of the Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale, and Tweeddale constituency at Westminster which is represented by Conservative Scottish Secretary David Mundell, who had previously contested the Holyrood seat, and his son Oliver was the victor here with a majority of 1,230 to edge out the SNP’s Joan McAlpine.

In Edinburgh Central, Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson pulled off a huge upset by picking off the seat from the SNP with a very slim majority of 610. Another surprise was in store up north in Aberdeenshire West, where they flipped another seat from the SNP – with candidate Alexander Burnett surging ahead with a majority of 900. Back in the southwest, Galloway and West Dumfries was held by the party under Finlay Carson with a majority of 1,514 following the retirement of the sitting MSP Alex Fergusson. Following this, the Tories completed a sweep of the border constituencies by holding on to Ettrick, Roxborough, and Berwickshire under John Lamont with an increased majority of 7,736 and 55% of the vote. Altogether, it was their best constituency result in Scotland since 1992 (when they had eleven) and even the map from that year looks similar in terms of Tory blue on it.

Throughout Scotland, the Tories made significant gains which failed to produce more constituencies MSP’s, but having increased their vote in almost every constituency, they were rewarded with a boat load of new parliamentarian’s courtesy of the regional list vote – 24 in all, and they came out on top in five of the eight electoral regions. This made for a combined total of 31 Conservative MSP’s, which is their highest-ever haul at Holyrood and placed them in second place – becoming the new “Official Opposition”.

Meanwhile for the Labour Party, which had not only been the Official Opposition, but had been in power from 1999-2007, the results were very unfortunate, to say the least.

Early in the night, by became all but clear that the party would lose its remaining Glasgow seats at Holyrood – having lost all of them at Westminster last year – to the SNP. Eventually, many of the other Labour seats fell to the SNP, with Eastwood being the exception, to the Tories. For that matter, the Tories came second in former Labour heartlands such as Clydesdale, and the party dropped to third place in these areas where they once could expect solid and predictable victories in any given year. The scale of the defeat resulted in the loss of several good Labour MSP’s whose experience and contributions will be missed.

In the face of this however, there were some bright spots for the party. In East Lothian, former Scottish Labour leader Iain Gray looked to be unseated as he defended a 151 vote majority against the SNP in a seat whose UK parliamentary equivalent had gone to the SNP last year. However, he managed to not only hang on, but actually grew his majority to 1,127 votes in the face of a Tory surge which may have come at the expense of the SNP and aided Gray along the way.

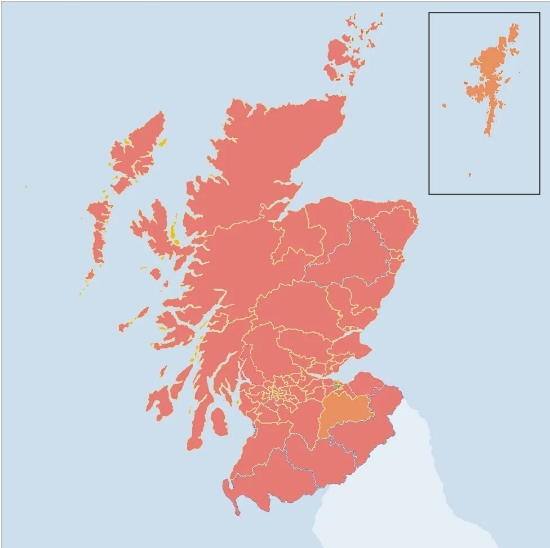

The changes in support for Labour from 2011 to this year's election. Greener areas indicateincreases in support; redder areas indicate decreases in support. Only Labour's win in Edinburgh Southern produced a solid increase. Image Credit: BBC; Graphics modificationand overlay by Stephen McGroarty

In contrast, Jackie Baillie barely held on to her Dumbarton constituency on the western side of the county with a greatly reduced majority of only 109, which may well have been aided Baillie’s defense of the workers at the Royal Navy’s nuclear submarine base at Faslane (in her constituency). At the very least, this highlights the need to vote, for every vote counts.

Meanwhile, Labour’s Daniel Johnson was able to gain Edinburgh Southern from the SNP with a majority of 1,123 and a good swing to Labour. It's perhaps fitting that Labour did well here given that it was the people of the UK parliamentary equivalent of this area (Edinburgh South) which had re-elected Ian Murray, the only remaining Labour MP in Scotland.

With only these three constituencies, Labour (including its leader, Kezia Dugdale, who failed to gain the Edinburgh Eastern constituency from the SNP) depended on the regional list vote to give them a decent amount of MSP’s at Holyrood – 24 in all, which represents their smallest representation since the advent of devolution, and the third place finish was their worst electoral performance in Scotland since 1910.

Of course, the SNP was still on top and remains in government for a third term, but without a majority as in 2011. This makes for a parliament that is more colorful, diverse, and representative of Scotland, as was intended when the voting system was put in place to prevent outright majorities of any party, so the SNP will be the largest of five minority parties at Holyrood. Even with the Greens at six seats to provide a nominal pro-secession majority with the SNP, there is no guarantee that the Greens will become lapdogs for the SNP, certainly not on all issues, and so there is every chance that the SNP may have to make deals with the (wicked) Tories – especially on taxes, where the two parties offered similar polices in their respective manifestos. Indeed, it would appear that the SNP’s broad church will be put to the test more than ever before, and combined with the new Conservative dynamic, we may also find out whether Scotland really is so vastly to the left of England that it necessitates the break-up of Britain, or if it is something which has a grain of truth, but is more likely a debating tactic used to manufacture grievances and advance the secessionist cause.

Furthermore, in the face of the sheer numbers of the SNP, there were significant swings against them in several of the constituencies that have been won by them in recent years, as well as the ones that have been their heartlands since the 1980’s and 1990’s. Some of these places were once reliably Tory before the SNP displaced them, and the Tories have since tended to come in second place in most Westminster and Holyrood elections. They were also the places with tended to vote overwhelmingly against the SNP’s landmark policy of separation. At this election, there were huge swings to the Tories from the SNP in Perthshire, Banffshire, Angus, Morayshire, and Aberdeenshire.

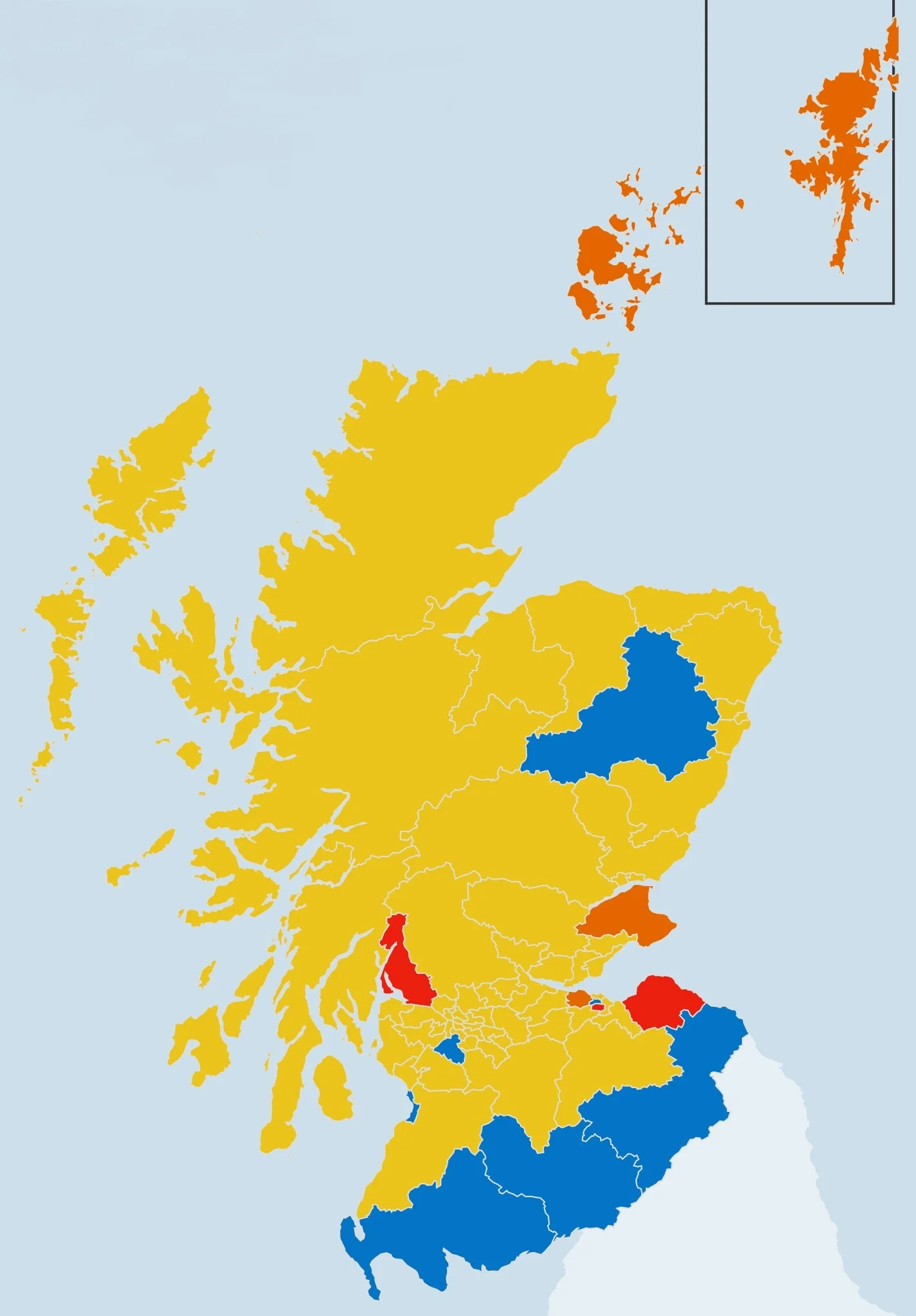

The changes in support for the SNP from 2011 to this year's election. Greener areas indicateincreases in support; redder areas indicate decreases in support. The biggest decreases came from the northeast and Tayside. Image Credit: BBC; Graphics modificationand overlay by Stephen McGroarty

In Perthshire South and Kinross-shire, the seat held by SNP Cabinet minister Roseanna Cunningham, there was 9.5% swing from her party to the Conservatives; nearby in Angus South, the SNP’s Graeme Dey was re-elected with a reduced majority of 4,304 against a 12% Tory swing; up in Moray, the swing from the SNP to the Tories was a whopping 15% as Richard Lochhead, another Cabinet minister, hung on with a reduced majority of 2,875. Most significantly, though Deputy First Minister John Swinney was re-elected as well, he experienced a 12% swing to the Conservatives in his Perthshire North constituency, which left him with a majority that had been reduced from 10,353 to 3,336 against Murdo Fraser.

Similar swings to the Tories were seen in other areas, such as Banffshire and Buchan Coast, Angus North and Mearns, Aberdeenshire East, and in the case of the aforementioned Aberdeenshire West, the Tory swing was big enough to wrest the seat from the SNP. Meanwhile there were swings to the Liberal Democrats in former strong areas such as Caithness, Sutherland and Ross, as well as Argyll and Bute.

Some of this may have been the result of former Tories and Liberal Democrats returning to their old parties from the SNP, but other vote changes may also have been due to tactical voting, as Alex Massie observed when he noted how the LibDem vote fell in the Borders and Aberdeenshire, only to have it rise substantially elsewhere, such as in North East Fife and Edinburgh Western. Indeed, if some places had a stronger swing against the SNP or more voters switched tactically, the SNP would have lost several more seats, including Swinney’s and Cunningham’s.

Overall, it was a decent result – possibly the best one in the circumstances – for those who support keeping the UK together. In terms of total votes, the Liberal Democrats, Conservatives, and Labour collectively received 52.4% of the popular constituency vote compared to the SNP’s 46.5%, or 1,194,343 votes against 1,059,9897 for the SNP. The three parties also out-polled the SNP on the regional list vote 47.2% to 41.7% (1,082,425>953,587), though with the Greens factored in, the pro-separation percentage rose to 48.3% and 1,104,103 votes. Even so, with the loss of six SNP seats (and the one belonging to the late Margo MacDonald as an independent), the number of pro-separation MSP’s fell from 72 to 69 – the same number of seats the SNP won five years ago – whilst the number pro-Union MSP’s rose from 57 to 60.

It must be remembered going into this election, it had been thought to be a foregone conclusion that the SNP would not only keep its majority, but also extend it to greater proportions than what had been achieved in 2011. In terms of constituencies alone, some projections had Labour losing all of its seats and indeed, the SNP vote appeared so strong as to threaten a wipe-out everyone but themselves in all 73 constituencies – leaving the other parties clamoring for all regional list seats. If it were that bad, the only seats given the best chance of surviving such an SNP tsunami would have been Shetland for the LibDems and Ettrick, Roxborough, and Berwickshire for the Tories.

As it was, this did not happen, and all three of the main pro-Union parties exceeded expectations through a mixture of SNP support perhaps peaking and cooling off, the rise of the Greens to take votes from the SNP, some tactical voting, and a great effort at old-fashioned dogged campaigning on the part of the Conservatives, Labour, the LibDems, and by pro-Union campaign organizations, who have all taken a beating over the last nine years of SNP dominance. Indeed, perhaps the best outcome of this election was the not only the break with absolute SNP domination, but that it also, as Brian Wilson observed, broke the “spell of Nationalist invincibility” and ought to take a second referendum “off the agenda since there is no plausible mandate for one.” Indeed, it may have been the thought of a second referendum which caused many voters to turn out against the SNP in the final weeks of the campaign.

The new constituency map is vastly more colorful than most projections had shown going into election day on May 5th. Image Source: BBC

If over the term of this new “rainbow” parliament, the political battles can be shifted away from the constitution, there will be opportunities for the three parties to grasp for better results down the line. For Labour, it was down, but not out, and Wilson pointed to the Dumbarton result as showing the way forward with a “strong candidate and a good story to tell” on issues that matter to people, like jobs, public services, health, and education. For the LibDems, they can hold their heads high winning two constituencies against the odds and look forward to developing their own narrative for the future. As for the Tories, they have been perhaps detoxified at last, but should be careful to not get ahead of themselves. Much of their resurgence came at the expense of Labour, and if they intend on holding this support and gaining more in the future, they need to offer something to the voters beyond defense of the Union. As Wilson observed, they’ve already started with their stance on not raising income taxes when they are devolved in full to Holyrood next year, and this he believes, was their biggest selling point, “more even than the constitution.” As the SNP possibly finds it more difficult to ride the low tax and anti-austerity horses, and more generally, being all things to all Scots, there will be openings for all three parties to take as different factions of the SNP may become dissatisfied with the party as a whole. (No wonder they want to get on with their summer secessionist initiative.)

This election may have been a turning point, and in short, all three parties need to build on the current results, consolidate them, and work on unseating the SNP in other areas next time around, so that Scotland and the United Kingdom overall can move forward.