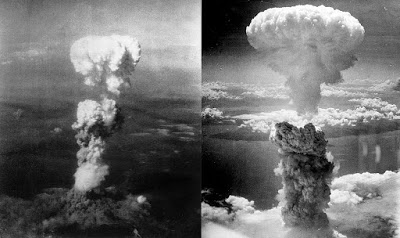

The End of WWII and Nukes Today

/The goal for our world is to ensure that another

Hiroshima (left) or Nagasaki (right) never happens again.

Image Credit: George R. Caron and Charles Levy (Public Domain) /

Combination by Binksternet via Wikimedia Commons cc

Seventy years ago, World War II came to an end with the surrender of Japan, though it was not until September 2nd when the formal documents of surrender were signed aboard the USS Missouri.

For many – particularly in Europe – it was the end of a nearly six year long ordeal that had begun with the invasion of Poland by Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany on September 1, 1939. In the Pacific, the conflict had its roots in the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria in China, while for the United States, the war was brought on by the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan on December 7, 1941.

But regardless of when hostilities started for different parts of the world, when Japan’s surrender was announced, everyone knew that it was all over, and that there was peace once again. The day was marked with euphoric and rapturous celebration, with enormous crowds gathered in New York – where thousands jammed Times Square;London – where the future Queen Elizabeth and her sister joined the masses around Buckingham Palace and Piccadilly Square; Paris – where the people celebrated their liberation from the Nazi regime, and in so many other places (big and small) throughout the world.

It became known as Victory over Japan (VJ) Day and seventy years later, it remains one of the most iconic and significant moments in history, and the commemorations have rightly honored the fallen who gave the ultimate sacrifice for the world in which we live today. They have also honored the people who made it back home to tell their stories – people whose numbers are dwindling day by day. They have also provided a period of reflection on the war and what it means for us today going forward.

This particularly includes the way in which the war was ended, for the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to force Japan into an unconditional surrender was one of the most controversial aspects of war, which has been hotly debated ad nausuem since they were dropped and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Was it necessary? Was there another way to end the war? Were the casualties worth it? Would the world have been safer if not for nuclear weapons?

I will not discuss these in detail here as they go beyond the scope of this post. However, it should be noted that the dropping of the bombs by the United States likely resulted in a more swift end to the war than had the Allies been forced to resort to other measures, such as a full scale invasion of the Japanese islands, which would have dwarfed the Allied effort on D-Day the year before.

Mercifully, these were the first and last times that nuclear weapons had been used for warfare in our history. Their immediate destructive power, combined with the long-term health effects, have arguably helped to ensure that there has not been a global conflict on the scale of the Second World War, because everyone knows that such a conflict will likely involve nuclear weapons, which were eventually obtained by the Soviets and other major world powers soon after.

But it was not just the proliferation of nuclear weapons that became an issue as more countries obtained them; it was also the fact that they were becoming increasingly powerful – like the hydrogen bomb – so that multiple Nagasaki’s could be contained within only one of them. Worse still were the dizzying number of weapons as the Western powers lead by the United States and the Communist powers lead by the USSR gathered vast stockpiles, so that by 1960, there were enough of them to destroy the entire world six times over.

It was a policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (with the appropriately acronym M.A.D.), and Japan’s emperor, Hirohito, alluded to this in his radio address to his people announcing the surrender of the Japanese Empire, when he talked of a “new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage” which would not only destroy Japan, but also “lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Not only was this arms race mad, but it was also terribly expensive – with the cost of building and maintaining these weapons and their massive support systems eating deep into national budgets. At some point, people began asking: “why do we have all these mass-destruction devices”? It became increasingly apparent that there were too many of them and – quite sensibly – that it would be virtually impossible to use all of them anyway.

And so began the long and gradual draw down of these gravely dangerous weapons. From a high of nearly 70,000 active warheads in the mid-1980’s, as of last year, there were only around 4,000 active and 6,000 inactive warheads – making for a total of just over 10,000 nuclear warheads in the world – with the United States and Russia owning the lions share of these, and in time, it is hoped that the numbers will decline still further.

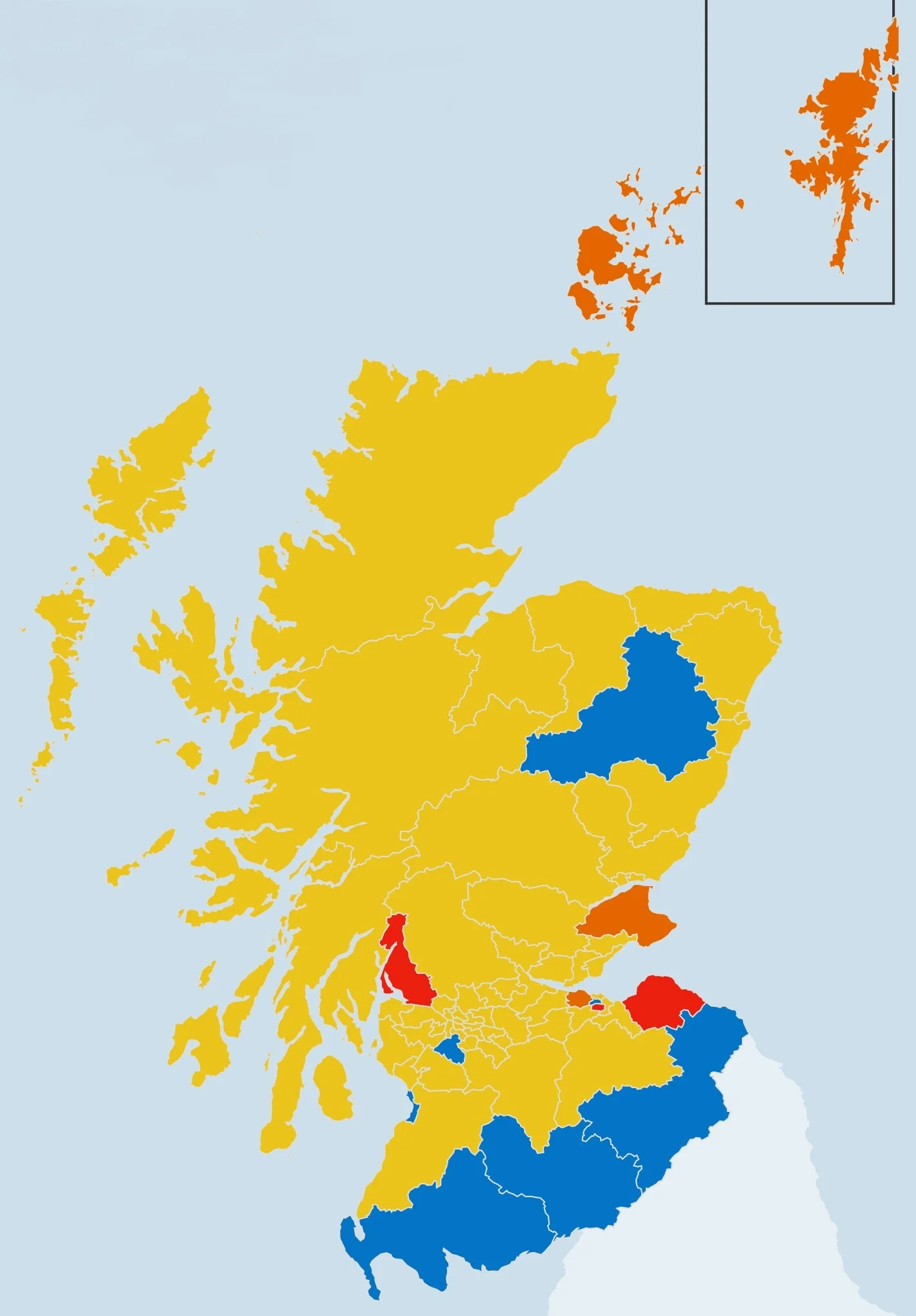

For its part, the United Kingdom possesses 225 of these weapons, of which 160 are currently active, and the country exercises its capability in a sea-based capacity via the Trident program of nuclear submarines operated by the Royal Navy based at Faslane along Gare Loch near the River Clyde – about 30 miles from Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city.

Nuclear weapons in general have been contentious for several decades ever since the development of the Polaris system in the Holy Loch in the 1960’s, and has particularly been used by the SNP as a means to advance their goal of breaking up Britain. Throughout the referendum campaign last year, the pro-independence campaign and its supporters were peddling the idea that with independence, Scotland could get rid of Trident (while still being part of NATO, a nuclear-tipped alliance) and save billions of pounds to be used for purposes such as health and education.

Scotland voted to keep the Union together, but the SNP has been consistent in their opposition to Trident – with members referring to it as “obscene” and an example of “Wastemonster” spending money on the wrong priorities. Still others object to the Trident submarines and warheads being based in Scotland, and believe that they were placed there so as to be far away from England and London in particular. A common refrain is: “If Westminster likes Trident so much, why don’t they place them along the River Thames?”

Her Majesty's Naval Base, Clyde (HMNB Clyde) at Faslane.

Image Credit: Public Domain

In truth, Trident’s location has more to do with strategic ability more than anything, for Faslane and the area along the lower Clyde is the best deep-water harbor in Britain facing the Atlantic and is well-suited for the submarines to slip in and out of the Atlantic with a lower possibility of being detected. This has nothing to do with treating Scotland unfairly or putting Scotland in a position to be bombed so that London can be spared, for the reality is that given the UK’s size, a modern nuclear weapon – with long-term health effects included – could wipe out much of the country, including the “protected” capital city, so it matters not where Trident is located in this regard. However, it does matter that it is placed in a location that gives the Royal Navy the best strategic advantage, and that location just happens to be Faslane.

Furthermore, the much-touted £100 billion cost for the new generation of Trident is to be spread over 30 years, and during that time, a lot of that money will be going to maintenance and paying the employee's – many of them with specialized engineering skills – who earn their keep at Faslane. Over the course of Trident’s lifetime, this will result in tens of billions of pounds being injected into Scotland’s economy, and in particular, the local economy around Faslane as money goes into paying for food, housing, mortgages, transportation, clothing, and other needs and desires. Some of the money is paid toward taxes and eventually finds its way into the coffers of the Scottish Government to fund the activities under its control.

So when the SNP talks about opposing Trident, they are effectively talking about opposing a critical piece of the economy, and with no concrete plan on what to do with the workers who have been trained in this area.

Of course, there are some people who will oppose nuclear weapons and Trident in particular no matter what. They point to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and believe that such weapons – with their destructive potential – have no place in the world at all, and need to be abolished. The SNP in particular wants Britain to unilaterally disarm.

This is a noble goal, and I for one would love to live in a world without nukes or any weapons of mass destruction. However, unilateral disarmament is unhelpful because there will still be others with the weapons, and so long as that’s the case, Britain should hold on to Trident. It’s not about what Britain can do with the weapons, but rather about the very existence of the weapons and the technology. This sentiment was expressed when General Omar Bradley discussed developing the H-bomb with President Harry S. Truman, and said that he could conceive of no military objectives that could be achieved with it, except for utter death, ruin, and desolation. He further said that these were not weapons, but “instruments of genocide.” However, he advised Truman to go ahead with the bomb because “for the other side to have it, and for us not to have it, would be intolerable.”

It may seem paradoxical, but the whole point of having the nukes is to prevent from having to use them (and to prevent others from using them against you), which is why it is called a “deterrent” and why there is an argument that full scale global wars have been prevented since 1945 because of this.

However, even if nuclear weapons were abolished from the face of the Earth, the technology and know-how will remain, and you can bet that somebody somewhere will want to use these at some point (unless you were to eliminate all nuclear physicists and burn every piece of written reference to nuclear technology).

The best that we can do is to promote multi-lateral disarmament among all countries that have nuclear weapons, and to prevent other countries from obtaining them altogether. As has been mentioned above, there has already been a massive amount of disarmament in the last thirty years since the height of the Cold War. Perhaps by the end of the 30 year period for the new generation of Trident, the number of warheads will be reduced further to the point that Britain may no longer need a deterrent, or if it does, then it may be a scaled-down and less costly one. The same idea applies to the US, Russia, France, China, and other nuclear powers, so that the threat of nuclear conflict is curbed and so that scarce resources can be put to other uses.

In the end, no one likes nuclear weapons. I repeat, no one, and I look forward to a world without them. Indeed, perhaps it would be nice to go back in time and prevent their creation. However, we must live with the reality that they are with us, and we have to do our best to ensure that that are never used again for any purpose.

For Britain itself, the country’s real influence may be more thoroughly expressed through its soft power, though it should always keep its hands close to its tools of hard power – both conventional and unconventional – in case they should ever be needed. In other words, “speak softly, but carry a big stick.”

A recent example is the recent nuclear deal with Iran, which among other things, proposes to open Iran up to trade with Western powers (including Britain, which helped to negotiate the deal) in the hope that this trade will eventually lift the Iranian economy, foster better relations, and therefore make Iran less likely to pursue nuclear weapons in the first place, and also make nuclear war in general less likely.

If Iran reneges and fails to hold up its end, then Britain and the other powers may have to reach for the “hard power” options, including the use of nuclear weapons, in order to deal with Iran. If however, the deal succeeds, this will be good for Iran, good for Britain, and good for the world, so that hopefully the horrific events 70 years ago remain unique in the long view of human history and so that a sustained peace can be achieved.