Glimmer of Hope? The State of the Race for Holyrood (and Secession)

/This year's election won't only decide who takes power at Holyrood, but will also likely set the trajectory of Scottish politics for perhaps another decade. Kim Traynor via Wikimedia Commons CC

With the Scottish parliamentary elections only three months away, a new YouGov poll for The Times has provided some interesting findings which may provide some hope for those who support the Union and are opposed to the SNP.

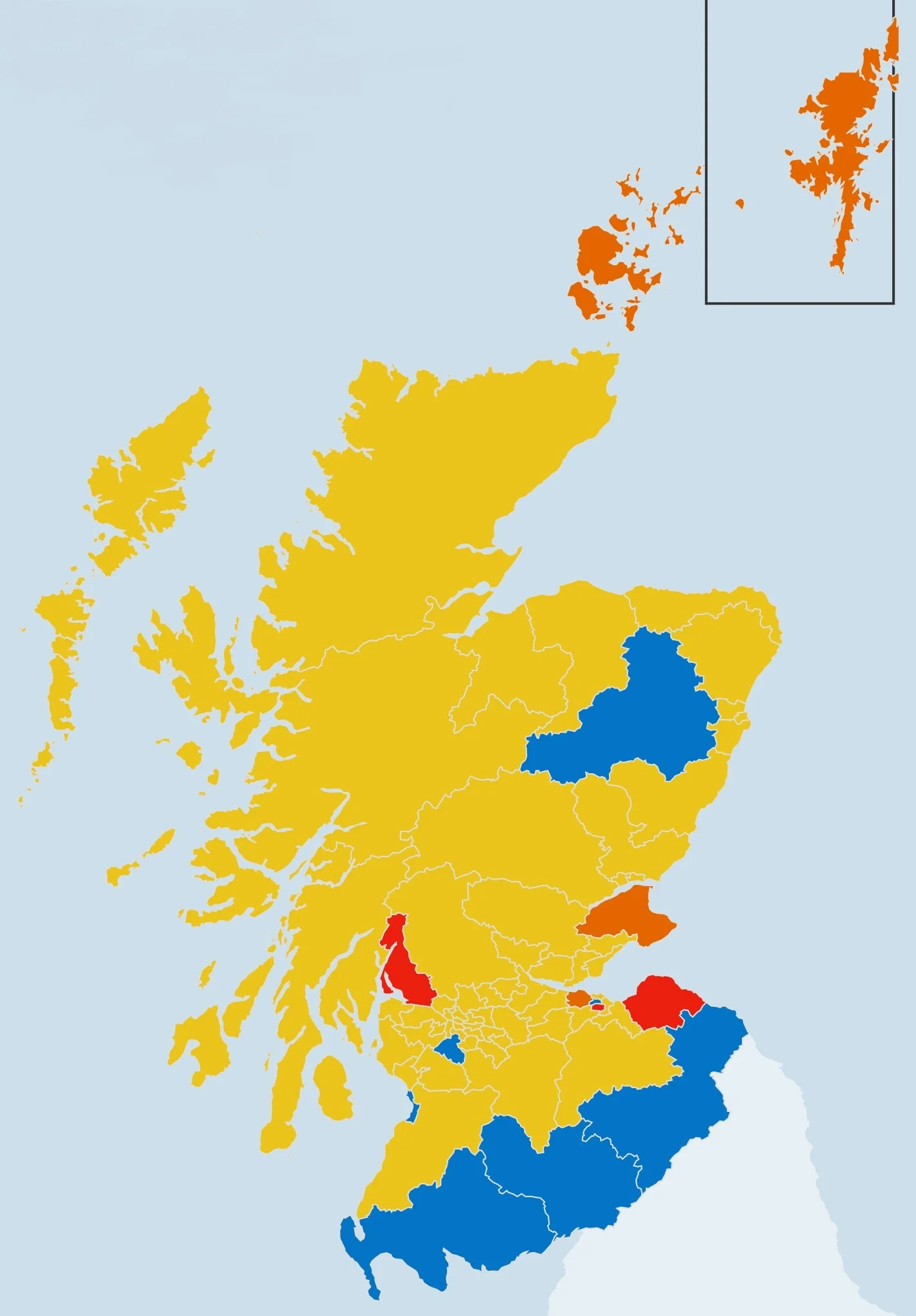

Firstly, with regard to the election itself, the SNP still leads the way voting intentions with 50% in the constituency vote and 42% in the regional list vote, which according to the Scotland Votes election calculator, translates into 69 seats – the exact same number the Nationalists won five years ago. They would still have an outright majority in a legislature supposed to be designed against such outcomes and be elected to an unprecedented third term in power.

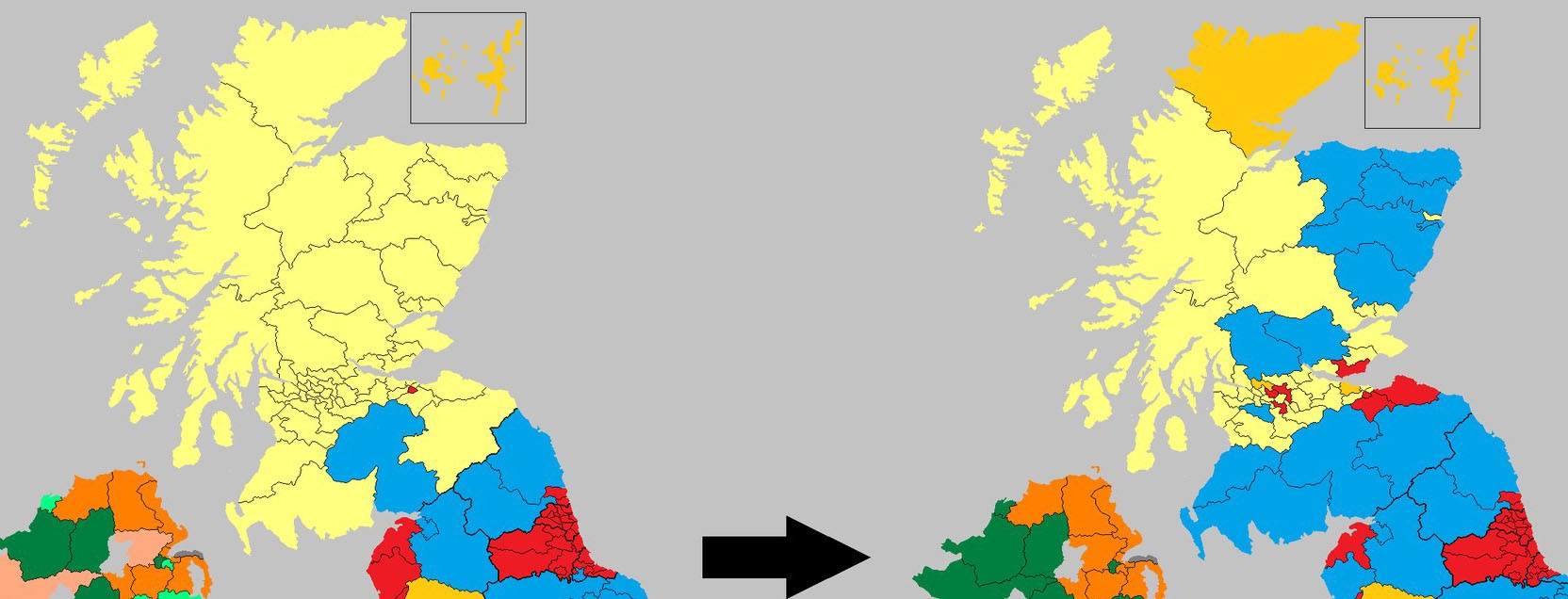

However, this poll is a bit different than previous polls in that it shows comparatively low numbers for the SNP. Polls back in the late summer and fall were showing them getting in excess of 50%, sometimes as high as the upper 50’s and lower 60’s – a reflection of the ascendancy of the Nationalists when they won 56 of 59 Scottish seats in the House of Commons in May. Even now, another recent poll by TNS shows them with 57% in the constituency vote and 52% in the regional list vote.

Nevertheless, it may be fair to ask whether the SNP has more-or-less reached its ceiling, whether it has maxed out its support among the electorate, and has nowhere to go but down. The answer to this will have to be deferred until after future polling, and perhaps even, until the election itself takes place in order for us to know where the SNP really stands among the voters. With the current polling figures from YouGov, the party will win 69 seats – the same number they won in 2011, which may appear to be a disappointment in comparison to the net gain in seats predicted in other polls.

Part of the reason for this is that the proportional part of Holyrood’s election system (based on the regional list vote) works against the party that does well in the constituency vote, and the SNP is projected to do really well in that area – capturing all but eight of Scotland’s 73 Holyrood constituencies according to the Scotland Votes election calculator. As a result, the calculator projects that the SNP will get only four regional list seats on 42% of the vote, which leads to the other reason the party may do no better than in 2011: minor parties.

There may well be some pro-separation voters who will vote for the SNP in the constituency vote – knowing that the first-past-the-post system punishes smaller parties such as the Greens – but then lend their second (regional) vote those small parties in the knowledge that they will register better in terms of proportionality. As such, the Greens and the Scottish Socialist Party hold 6% and 2% respectively of the regional vote – likely at the expense of the SNP, and for their part, the Greens stand to pick up three seats for a total of five, which means that the pro-independence majority will stand at 74 seats.

In the face of this, what is there to say about the main pro-Union parties who will have 55 seats among them if this poll were repeated on Election Day?

For Labour, the outlook remains as dismal as it has ever been since the referendum. The party which only ten years ago had led a coalition government in Holyrood, and whose grip on some parts of Scotland was so tight that votes were said to be weighted and not counted, is sitting at 19% of the constituency vote and 20% of the regional vote, with much of their traditional voting base having voted Yes in the referendum and now voting SNP. If this result were to be replicated in May, Labour would lose all of its constituency seats, and will depend on the regional vote to give it 25 seats. In fact, Labour will take the lead in regional seats even though the SNP carries 42% of the vote, but again, the proportional system will work against constituency-heavy SNP.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives will have the same regional vote share, but end up with 19 seats – six less than Labour. However, the Tories do have a one point edge in the constituency vote, and this – combined with the relative collapse of Labour and the Liberal Democrats – is projected to be enough for them to win six constituency seats. Among them is Labour-held Eastwood, whose UK parliamentary equivalent was a Tory stronghold for most of the 20th Century and was once the safest Tory seat in Scotland until Jim Murphy won it in the Labour landslide of 1997.

That election resulted in the complete wipeout of the Conservatives in Scotland in terms of seats in the Commons, and since 2001, they’ve only held one seat at Westminster and as much as 18 at Holyrood (and currently only 15), thanks to the perception of them being “toxic” during and following the years of Margaret Thatcher. But now they are poised to win 25 seats in May, and this is attributed to the leadership of Ruth Davidson, who is judged to have had a good referendum by campaigning for the Union and putting on a fresh face for the Conservatives. She is currently rated as doing well as party leader by 40% of YouGov poll respondents, as opposed to 36% who say she is doing badly.

Among those who believe she is doing well includes 46% of Labour voters, which explains another reason for the recent Tory ascendancy in the polls: disillusioned Labour voters who are planning to vote Tory because of Labour’s shift to the left under UK party leader Jeremy Corbyn and Scottish leader Kezia Dugdale’s invitation to those who voted for separation but who may otherwise agree with Labour on everything else save for the constitutional question. They see this as Labour lessening its support for the Union - a point with which I respectfully disagree - and therefore see the Tories as the “only” Unionist party who will stand up against the SNP and speak for Scotland’s place in the United Kingdom.

Much the same can be said about the Liberal Democrats, who have been paying the price for going into coalition with Conservatives following the 2010 UK general election which resulted in a hung parliament. While Labour and the Tories battle it out for second place (and bragging right for being the official opposition), the LibDems too have, under Willie Rennie, made an invitation to Yes voters to join their party and vote for them regardless of their difference on the constitution, because like with Labour, many of their former voters voted Yes and/or for the SNP. They currently sit at 6% in the constituency vote and 5% in the regional vote, which will be enough for them to hold on to the five seats they currently have, including their only two constituency seats of Orkney and Shetland – which have been in Liberal/Liberal Democrat hands for much of the last century.

However, these results are not set in stone, and it is possible for the three parties to at least prevent the SNP from obtaining another a majority. The reality is that the SNP has been successful in picking off voters who had traditionally vote for the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats through slippery and slick triangulation – shape-shifting when needed to appeal to certain groups of voters in certain areas. So each party needs to go forth and present itself as the SNP alternative in the parts of Scotland in which they are still strongest. For Labour, this means concentrating on the Central Belt and Lowlands regions; the Borders for the Conservatives; the Highlands and Islands for the LibDems; and the northeast for the Tories and LibDems, with Aberdeen, Dundee, and the areas surrounding them also being potential targets for Labour.

However, it’s not just about areas, but issues as well. The ongoing row over local council funding cuts has sparked a debate on taxation and how much people should be taxed. On this Labour and the LibDems have taken the side of using Holyrood’s existing powers to raise taxes to improve public services, and according to the YouGov polling, most voters support this proposition, including a clear majority of SNP voters. Another byproduct of the local government funding debate is whether the SNP’s nine year old council tax freeze needs to be brought to an end, as the Scottish Government’s own independent advisor on poverty has recommended. In his analysis, Professor John Curtice said that the freeze “may be approaching the end of its politically useful life, as well as, perhaps, its fiscally sustainable one” as council budgets and services come under increasing pressure and jobs are at stake. 54% of voters now wish to see council tax raised in order to improve local services – effectively ending the freeze.

This may put the SNP in an uncomfortable position as the council tax freeze has been one of its landmark policies and is very likely reluctant to campaign on raising any taxes, lest it lose the middle class and upper class voters who have been the source of its electoral strength, thanks to them disproportionately benefiting from the freeze and other policies such as free prescriptions and free university tuition. It has certainly found itself on the same side of the Tories on whether taxes should be increased, and Labour under Dugdale is certain to use this point throughout the campaign with at least some belief that the public does stand for taxes to be increased.

Whether this will work in practice remains to be seen. As Euan McColm said in The Scotsman, the agenda of exposing the Nationalists as faux radicals – “claiming to be left-wing while acting centrist” – may “work if the voters who are keeping the SNP in power were at all interested in hearing that they’ve been conned.” The problem of course, is that some within the middle classes who decide elections and who vote SNP do not see themselves as being conned because as far as they’re concerned, it is they who have benefited pretty well from SNP policies, which have been cloaked under the guise of universalism. Despite what Brian Wilson refers to as the “unctuous self-praise about what a uniquely caring people we are, delighted to pay a little more to help the weak in our midst”, the reality in Scotland according to McColm is that “regardless of the left-wing rhetoric that we hear so often in our political debate, voters remain cautious and self-interested” (just as they are in England), and both the SNP and Labour – more-or-less occupying the same political space save for the constitution – know this.

However for Labour, this is about setting itself apart from the SNP as well as the Tories – perhaps in an effort to capture some of their traditional working class vote who may feel conned that the SNP stands with the Tories on not raising taxes. For their part, the Tories have made some noise about the SNP not ruling out tax increases in the future, especially when it’s expected that Holyrood will gain complete control over income tax rates and bands in 2017. On this, they will lay their hopes on picking off middle class support for the SNP. This will likely not put them into power any time soon, but like with Labour fighting for its political life, the Tories have to propose something to differentiate themselves from everyone else, including the LibDems, who under Willie Rennie have also proposed tax increases. With any luck, all three pro-Union may save themselves from losing a few seats and help prevent the SNP from attaining another majority, which is the best case scenario for them.

However, there is one definite ray of sunshine: support for separation – at least in this poll – is slipping. The last time YouGov asked the question in October, 49% of respondent declared they would vote No and 45% supported Yes; this time, there was a 51% response for No and a 43% response for Yes. With those who said “Don’t Know” and “Would not vote” taken out, this amounts to 55% No and 45% Yes – the same proportion from the actual vote in September 2014, which according to Professor Curtice, “is actually the lowest level of support for independence recorded in any YouGov poll conducted since the referendum.”

Looking at the internals, 91% each of those who voted Yes and No would do so again; 5% of those who voted Yes in 2014 would vote No in a second referendum, while 4% who voted No would switch their vote to Yes. Breaking down by party, 99% of Tories, 94% of Labour, 95% of LibDems, and 12% of Nationalists at last year’s general election would vote No again; for this year’s Holyrood election, this stands at 99% Tories, 90% Labour, and 8% SNP (the LibDem figures were not available).

Seen another way, the Conservatives will win 38% of No voters, closely followed by Labour at 34%, the LibDems at 12%, and 13% among the SNP. All of this appears to indicate the support for the Union remains very strong among the three main pro-Union parties, while around 90% of SNP voters either voted, or will again vote, for independence. The only area for long-term concern is the 18-24 age group, who responded in favor of Yes by 55%-45%, while all other groups responded in favor of No.

At any rate, the YouGov polling shows that – at least for now – a second referendum is a distant prospect, if for no other reason than because of Nicola Sturgeon's own benchmark of having consistent support for independence at 60% or more in the polls for several months before going for it again. If she does go for it before the end of this decade and loses, it will mark a serious and near-fatal setback for the Nationalist cause with back-to-back defeats. It is therefore no wonder that some in the SNP are dreaming of an EU referendum scenario in which the overall UK votes to terminate its EU membership, but Scotland votes to keep it, so they use it as an excuse to call a second referendum based on that fact the YouGov polling currently shows Scots supporting the UK’s EU membership 66%-34%. Barring that circumstance, another referendum looks to be in the offing. As McColm further notes, after the election, Sturgeon will:

"have to maintain support while conspicuously not delivering that second referendum. With the focus off the constitution, perhaps flaws in the SNP’s domestic agenda (and these flaws do exist) will start to become apparent."

Nevertheless, the pro-Union parties need to step up their own game if they wish to definitively take a referendum off the agenda after May, which requires preventing the Nats – perhaps along with the Greens – from having a majority and at the very least, operating as a minority government and not being able to get through a referendum bill, just as they could not do from 2007-2011. Such a bill would be symbolic and non-binding as constitutional matters remain reserved at Westminster, but if it were to pass, it is difficult to see how Westminster – in the absence of formal rules regulating referendums – can stand in the way if that’s what the majority of Holyrood wants.

So the Tories, Labour, and the LibDems need to get out and campaign hard by focusing on the issues that matter to people beyond the constitutional arguments. Promises of avoiding a repeat referendum will not gain enough votes to prevent another SNP majority, but dealing with the day-to-day issues and concerns of people (such as health, education, and policing) and offering a positive alternative has the chance of at least making just enough people to think twice before voting for the SNP. Let the SNP wallow in the constitution while for example, council budgets tighten, services are reduced, and people are thrown out of work. Each party has their own strengths, and must use them to their advantage and fight like hell if they wish to upend the consensus narrative of this election year.