Still Together and the Path Forward

/The "Aerial No" in Edinburgh just days before the referendum.

Today would have been the day that Scotland became an independent country and when the United Kingdom would have been broken up.

Thankfully, it is not. The people of Scotland saw through the dubious, dodgy, and threadbare claims of the separatist case pushed by the Yes campaign, led by Alex Salmond and the SNP. The people debated and argued throughout a two year long campaign in which all of the issues were discussed at length. During this campaign, there was almost constant media coverage of the campaign and the issues at stake; there were claims and counter-claims – in print, on television and radio, on various online platforms. Indeed, with all the back-and-forth going on between the positions and people on both sides, it’s a wonder that many of us didn’t lose our heads!

It was an emotionally training and exhaustive campaign – the likes of which many of us had not ever witnessed – and the world watched to wonder if the United Kingdom was on the verge of dissolution. Indeed, as the campaign went into its final month, the Yes campaign caught up and it looked as though they might have had a shot at their prize.

In the end, after all the speeches, rallies, leaflets, ads, marches, bean counting, pronouncements, and flag-waving, on September 18, 2014, the people voted decisively to maintain the United Kingdom and to preserve over 300 years of history, heritage, and relationships – economic, social, cultural, and political. The people said quite politely and in a fair and legal democratic referendum: “No, Thanks”.

We should all be thankful for the result, for it spared Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom from unnecessary and untold upheaval on many fronts. A bullet was dodged and one of the greatest countries in the world was saved.

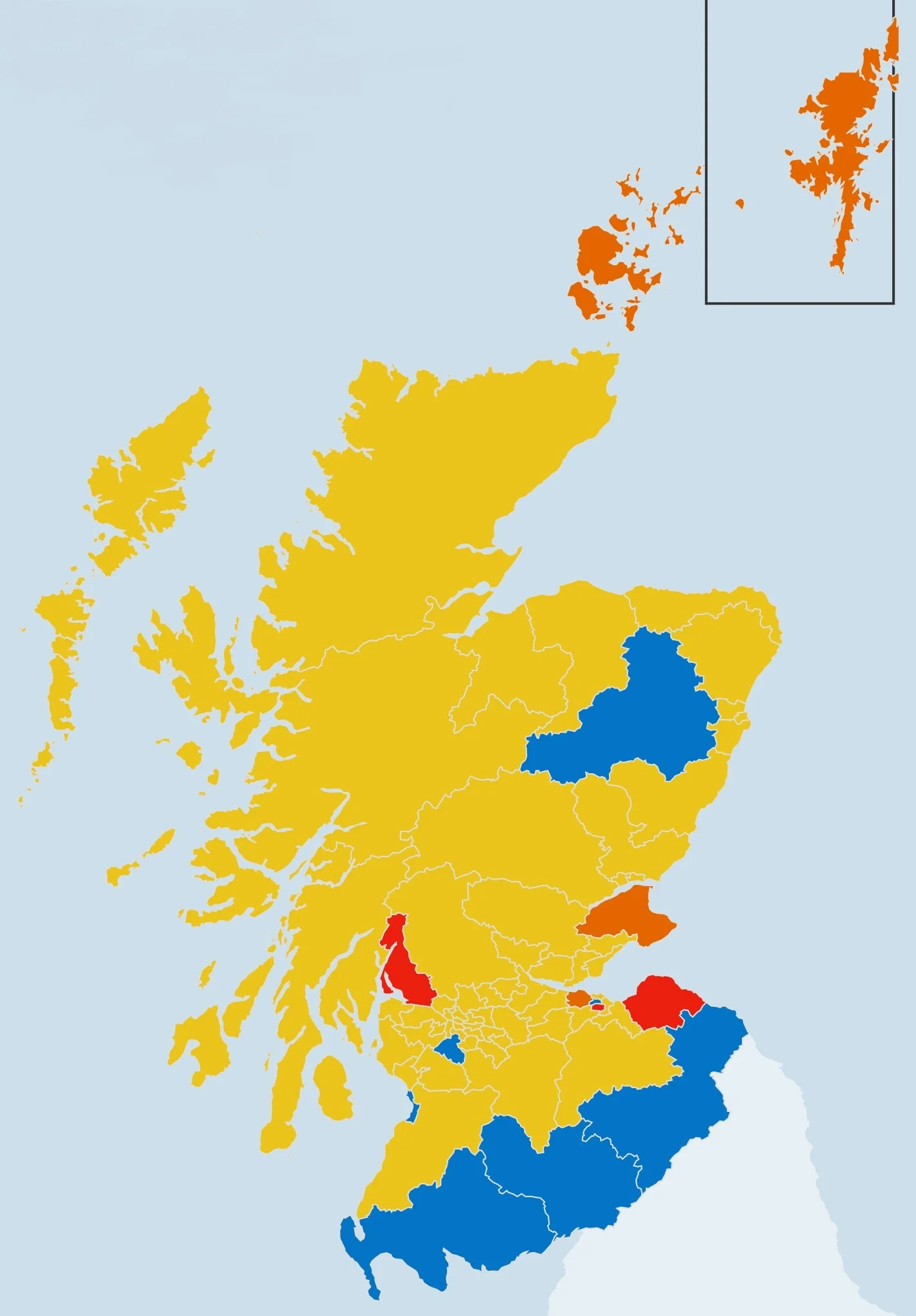

However, there’s no denying that the SNP – far from being mortally wounded – has gone on to dizzying heights as a political party. Successfully capturing the 45% of Scots who voted Yes and trading on the popularity of their new leader Nicola Sturgeon, they won all but three of the 59 UK parliamentary seats in Scotland at the General Election in May 2015 – becoming the third biggest group in the House of Commons and in terms of its membership, the third biggest political party in the United Kingdom.

Now, there appears to be little sign of them slackening in the opinion polls, and they are projected to win an unprecedented third term in government with another majority – thereby likely keeping the separation and constitutional issues at the forefront of politics in Scotland. Scores of voters who tended to vote for the three pro-Union parties have bolted to the SNP, and there are no indications that they are coming back soon.

In the face of this, the SNP’s opposition is divided between those parties – Labour, the Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats – with Labour and the LibDems at historic lows and the Tories seeing something of a small revival since their 1997 wipeout, but nothing in the way of providing the numbers and political muscle to provide a strong opposition by any single party.

In the circumstances – especially with most polls still showing a majority or dead-heat on the independence question – some people such as columnist Alex Massie have come to the conclusion that Scotland has too many parties, and that if the vast majority of Yes voters are fueling the SNP’s rise to around 50% in the polls, then it stands that No voters need to have a party of their own – a single “Unionist Party.” They believe that the pro-Union/anti-Union split and a focus on constitutional arraignments are the new norm and that, in Massie’s words, “the great political realignment spawned by the referendum is not over yet”, and in this vein they believe that a Unionist Party must be formed out of a merger of the three main parties and the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in order to give a proper voice to those who voted No, mount an effective opposition to the SNP, and “offer a plausible alternative to the SNP’s constitutional vision.” Given that the SNP is effectively (in practice, if not in rhetoric) a centrist party, a Scottish Unionist Party would run largely parallel to them and differ only on the national question. As Massie put it, the SNP and SUP would be “rather like Caledonian versions of Fianna Fail and Fine Gael [in the Republic of Ireland], parties sharing the same part of the political bandwidth, but ferociously opposed to one another.”

In many ways, I must say that this is an enticing prospect. There is sound logic behind, and in theory, would very much help at providing an effective answer to the SNP. The problem is that theory is just that – theory – and there are three main problems with the creation of a Scottish Unionist Party.

Firstly, how would it work in terms of political ideology outside of advocating for the Union? It may be easy to say that it would be a centrist party to appeal to most people, but realistically, how would it accommodate those members, activists, and voters from Labour, the Tories, the LibDem's, and UKIP? If you can't get the vast majority of those who voted No to back a Unionist Party because of differences over non-constitutional policies, then where will they go when their parties have been merged into it?

Secondly, how would it work in relation to the House of Commons? Would the party vote with a whip unto itself or would left-wing MP’s be able to vote with Labour and right-wing MP’s with the Tories?

Thirdly is the concern that a party whose raison d'être is “Unionism” will only entrench the referendum dividing lines and make for – and I say this with no disrespect – a Northern Ireland-type situation in which politics and society are perpetually focused on and organized around the constitutional issues. This “are you pro or anti UK/indy” dynamic plays into the SNP’s hands as elections become less about real policies and what is happening in the world.

Of course, there once was a Unionist Party operating in Scotland, but that party (which lasted from 1912 to 1965) was basically the Conservative Party in Scotland and took the Conservative whip at Westminster before formally merging with the Conservatives in England and Wales; a new (serious) Unionist Party would have to capture the vast majority of those who voted No from across the political spectrum in the Labour, Tory, and LibDem traditions. However, it is hard to see that happening; it was tough enough keeping the Better Together campaign rolling as a competent operation staffed and fronted by people who were (and still are) opposed to each other on virtually every other issue save for the constitution.

Now make no mistake: I am a head, heart, and soul supporter of the Union – economically, socially, culturally, and politically, and I dearly wish for the United Kingdom to survive as a country forever. However, I am simply not convinced that the creation of a new Unionist Party is the best way forward.

Most post-referendum studies have shown that among No voters, only around a third did so primarily out of affection for the United Kingdom and being British; much of the rest did so out primarily out of concern for their personal economic interest and because the case for separation was not convincing, which perhaps explains why some them do not label themselves a “Unionists.” Their support for the Union is not – at least primarily – driven by sentiment and the sense of historical connection to the rest of the UK. As such, they are not the type of people who support the Union come what may and appeals to Britishness and waving the Union Flag may not be helpful among them; they are the people who said that they would have supported separation if they were £500 better off individually, and so their support must not be taken for granted.

Many of them are primarily concerned about the economy and prospects for themselves and their families, and they were convinced in 2014 that they were better off within the United Kingdom. Who’s to say that at least some of them may not be convinced should another referendum be held – God forbid – within the next few years?

At the very least, polling ought to be done to find out what kind of support a Scottish Unionist Party would have, and especially if the vast majority of people from all three main parties are willing to join and vote for it. Without that polling however, I am willing to bet that with all of the practical obstacles facing it, an SUP will not likely gain traction as an effective counter-weight to the SNP.

Going forward, the best option in the long-term will be to support the existing Union parties, who need all the help they can get to recover themselves to respectable positions at all levels in Scotland, especially Holyrood. Indeed, as Holyrood obtains more powers over people’s lives, it will be incumbent upon each party oppose the SNP and offer viable alternatives to the people of Scotland, with a focus on making life better for people on issues such as education, policing, healthcare, welfare, transportation, housing, and – above all – the economy, and moving away from the constitutional issues as much as possible.

We are already seeing some rumbles of dissatisfaction within the SNP ranks, with the recent announcement on tax policy - keeping the top rate of tax in line with the rest of the UK - being just one area causing some consternation in some sections of the party. To be true, there may not be enough dissatisfaction with the SNP in time for this upcoming election, but it’s there, and Labour, the Conservatives, and the Liberal Democrats need to be ready for those who may become disillusioned and are ready to give at least one of those parties an audience. This, I believe, is bound to happen as the SNP stays in power over a longer period of time with more powers over people’s everyday lives than any previous administration at Holyrood and perhaps find it difficult to please it's broad church of socialists, neo-liberals, progressives, environmentalists, fossil fuel promoters, free-marketers, free traders, social democrats, and hard-core nationalist's.

However, this is not to say that the Union does not need defenders advocating on its behalf day in and day out, and that’s where campaign groups such as Scotland in Union (SIU) and United Against Separation (UAS) come into play.

UAS first came about during the referendum and played a major role in it as the “Vote No” page, and like its current name suggests, it is against breaking up the UK and has played more of role in opposing the SNP and pointing out its many contradictions and duplicity on several issues, while SIU came about more out of the aftermath and division caused by the referendum, and is more about promoting a positive message about Scotland and its place as part of the UK, and is not necessarily as much of an “anti-SNP” organization. As such, they are genuinely complementary in various ways – UAS is bigger with more “Likes” on Facebook and has more of an activist edge; SIU has more of a mainstream media presence, and conducts research and polling on Scotland and the Union. Broadly they have the same goal, but with just a slightly different approach.

Both of them are doing a good job with what they are doing, and last night, SIU held a special gathering to mark this day when Scotland and the UK as a whole dodged a bullet. Going forward, UAS and SIU need to continue on by promoting and supporting the UK, and the ideas that the UK is better for having Scotland and Scotland is better for being in the UK. Their success will be an end to the dominance of the SNP, as well as the reality that separation and nationalism are not good options for Scotland. The byproduct of this will be more Labour, Tory, and LibDem members in Holyrood and Westminster in a much hoped-for return to non-constitutionally aligned politics.

At an individual level, more people among us need to get involved with UAS and SIU, and volunteer their time leafleting, manning stalls on the streets, knocking on doors, having conversations with people, hosting/holding events, being active online, and generally doing all they can to help spread the word about the Union and its benefits to Scotland, along with how the UK in general is made stronger with Scotland. Part of this should be to make a social and cultural case for the UK in tandem with the economic case, so that there can be an even stronger case against the SNP – one that talks about the UK as a whole and how Scotland makes it what it is because of its people and many other contributions.

This is likely going to be a long-term effort which will require a lot of work and sacrifice. None of us wanted the referendum and all that has transpired since, but this is where we are, and we have to take this thing one day at a time. There will be progress and setbacks, but with time, I do believe that all of us can do something to make a difference in helping to keep the United Kingdom together in a positive, bold, and confident manner.