New Settlement Unfair, You Say? Stick with the Current One.

/The SNP is haggling over a new cash deal from Westminster. Image Credit: Howard Lake via Flickr cc

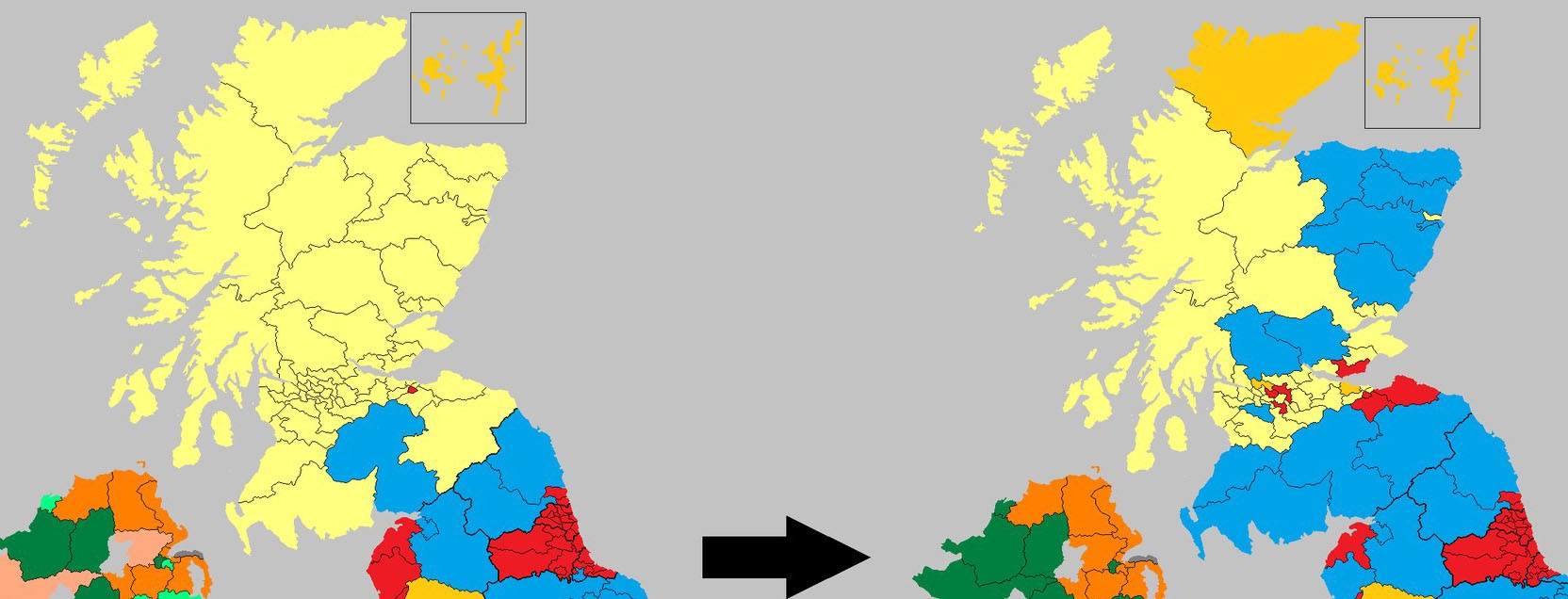

Through this week, there have been rumblings that the SNP may reject the “more powers” for which they have been agitating – and unconsciously concede that the United Kingdom has been good for Scotland.

This has been going for some time, but it really came to the fore last Sunday, when First Minister Nicola Sturgeon appeared on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show at her official residence of Bute House in Edinburgh for an interview which covered a range of topics that will affect the political landscape throughout the year.

Among the topics discussed was the new “fiscal framework” which must be agreed to by the UK and Scottish governments in light of the powers over income and other taxes and receipts which are set to be devolved to Holyrood in accordance to the Scotland Bill which was passed by the House of Commons last year. Basically, the new powers and the ability of Holyrood to tax within Scotland need to be offset with cuts to the block grant from Westminster which currently funds the Scottish Government, which is determined by the Barnett Formula.

Technically, the UK Government can bring the bill into force when it passes its final stages at Westminster, where the House of Lords is in the process of scrutinizing it. However, it is an established convention that Holyrood should give consent to such legislation with regard to the devolution settlement and the ability to increase (or decrease) the amount of legislative authority controlled by Holyrood. Thus, the fiscal framework must, at least according to the SNP, be completed by mid-February in time for MSP’s to scrutinize the overall devolution package brought about by the Smith Commission in 2014, so that it can be brought into effect before the Scottish parliamentary election in May.

In her interview with Andrew Marr however, the First Minister stated that there was “a long distance still to travel” in negotiations over the fiscal framework and warned that the UK Government must show “significantly more movement” on her demands for how the block grant is to be adjusted. Finance Secretary John Swinney has also stated that both sides are still a ways apart from a deal, and Sturgeon said that she will not “sign up to something that is unfair to Scotland” – effectively saying that her MSP’s (the majority at Holyrood) will vote to block the legislation and scupper the arrival of the new powers.

Now to be fair to the First Minister, there are understandable issues that need to be worked out to the best and fairest extent possible. As The Herald noted on Saturday, although the changes to the block grant “should be straightforward on day one”, it is how the grant is adjusted in the years and decades to come which is “proving hugely complex and contentious.” It continued by saying that “small shifts in the relative economies and populations of Scotland and the UK could result in major changes” which under at least one scenario, could result in Scotland being “hundreds of millions of pounds worse off.”

Again, these issues must be given due consideration in the pursuit of a deal that does justice for Scotland, the other parts of the United Kingdom, and the United Kingdom as a whole. However, this is what the SNP signed up for when they agreed to the Smith Commission recommendations in 2014. Yes, there was a “no detriment” clause to prevent Scotland and the rest of the UK from being better off or worse off as a result of the new constitutional arrangements, but it’s difficult to believe that this meant that Holyrood would continue receiving the same amount of public spending per person per year above the UK average.

According to The Herald:

“Mr Swinney favours a mechanism known as per capita indexation, which would protect Scotland if, as expected, its population grows more slowly than England’s.”

Leading economists agree the method would be the most advantageous for Scotland, potentially adding hundreds of millions of pounds to Holyrood’s budget within three or four years compared with other systems for adjusting the block grant.”

However, with the devolution of setting income tax rates and bands (and less money going to the Treasury in London), such a system “would be unfair on the rest of the UK as increasing amounts of income tax raised south of the Border would be used to fund services in Scotland” as opposed to reducing it, which would seem to be the logical thing to do.

Sturgeon says that she wants the new powers in the Scotland Bill, but the disagreement over the fiscal framework has the appearance of not wanting any of the consequences of having those new powers, as I wrote back during the tax credits debate at Holyrood last year.

Indeed, the Daily Record’s editorial that week is apt for today’s circumstances:

"Moan, moan, bitch, bitch, whinge, whinge. Their response has been as negative as it was predictable. A cynic might argue that the SNP don’t actually want those new powers because it makes them more accountable to the people of Scotland."

Therefore, one may wonder if this is an effort to stall the new powers from taking effect by setting out a negotiation that dooms the talks over the fiscal framework to failure. This thereby blunts the debate on the use of the new powers during the election campaign. Instead, the powers themselves and the fallout from the failure of an agreed framework will take up much of the campaign oxygen, which the SNP believes will benefit them and allow them to continue blaming Westminster and getting around the issues concerning their nine year record in government, which is not entirely sunny, to say the least.

Like fracking and other issues, the government appears to be putting off final decisions on them until after the election, lest they cause splits in the SNP’s broad church of socialists, neo-liberals, progressives, environmentalists, fossil fuel promoters, free-marketers, social democrats, small “c” conservatives, and hard-core nationalists.

Indeed, this has the hallmarks of former Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill when he explained why he blocked the extension of voting rights to prisoners in 2014, despite supporting the idea. It was he said, “the wrong thing done, albeit for the right reasons”, and for MacAskill, the right reasons were to “avoid any needless distractions in the run-up to the [independence] referendum, to deny the right-wing press lurid headlines that could tarnish the bigger picture.”

This time, the bigger picture is the election in May, and it may well be that the deal falls through now, but then the SNP suddenly signs up to it over the summer (after winning a second outright majority and unprecedented third term in Holyrood), with Sturgeon, Swinney, or another senior member solemnly stating – as they always do on these matters – that it doesn’t go far enough, but they’ll make do.

If this happens, they will have tested the delicate constitutional and fiscal system to destruction, but to what end?

When the First Minister said she would “not sign up to something that is unfair to Scotland”, her husband and SNP chief executive Peter Murrell tweeted this statement on Twitter, and this was followed by my fellow blogger Kevin Hague (@kevverage), who said: “you relentlessly claim we’re being hard done by the UK, but now you’re desperate to preserve the benefits of union?”

From this question by Kevin, I chimed in with a question of my own: “By implication, are they saying that the UK has indeed been fair for Scotland all this time?” Kevin responded in a retweet that it was “quite hard to avoid this conclusion.”

Logically speaking after all, if this new settlement is deemed unfair, what does it say about the current one?

Under the current system, the Barnett Formula automatically dictates the amount of public spending in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland based on adjustments to spending in England, so that when spending on health or education are changed in England, this changes the amount of public spending (known as “Barnett consequentials”) for the devolved governments of the UK.

It was created in the 1970’s as a temporary measure, but has all but become a permanent part of the UK constitution. With regard to Scotland as Brian Wilson noted in The Scotsman last week, it came about in the era of administrative devolution when responsibility for Scottish matters were primarily in the hands of the Scottish Office and the Secretary of State for Scotland in the UK Cabinet. With legislative devolution, the formula is the primary means by which the Scottish Government is funded – a “valuable legacy which Holyrood inherited”, says Wilson.

The formula has been heavily criticized for that fact that it typically results in more spending per head in Scotland than the UK average (and higher than all parts of the UK except Northern Ireland), but Wilson argues this is defensible “on grounds of geography, historic needs and indeed past distribution in the other direction.” On the last point, he refers to the three out of past 15 years when Scotland (on the back of high oil prices and revenues) paid more into the UK Treasury than got out, but adds that that in the course of time, the net flows of cash can go both ways so that it balances out in the grand scheme of pooling and sharing throughout the United Kingdom.

In the current circumstances, Wilson refers to Barnett as “a safety net which benefits Scotland” – this year to the tune of around £10 billion more than Scotland’s contribution to the Treasury. Despite the dramatic collapse in oil prices and revenue (only a small fraction of overall UK revenues), whatever is spent in the UK overall, Scotland gets a fixed share that (again) is higher than the UK average per person which explains the “bigger public sector” and therefore, “higher average wage rates.”

Furthermore, says Wilson, there is the matter of “dollops of additional money in the course of a year” which result from Whitehall spending increases for special projects and emergency needs. Here, he refers to the recent flooding that has taken place throughout the UK, so that when additional money was allocated for flood relief and recovery in England, Scotland automatically received an additional nine million pounds. Even more crucially, he pointed out that Holyrood stands to receive an extra £1.5 billion in Barnett consquentials resulting from the proposed HS2 project in England. Still further, if a third runway at Heathrow is constructed, even more cash will get sent to Holyrood, and just this week came the signing of the £500 million City Deal for Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire, which will be jointly funded by the UK and Scottish government’s (which is similar to some joint federal and state initiatives in the United States, such as the harbor deepening project in my hometown of Savannah, GA).

Once Barnett cash (funded by taxpayers throughout the UK, including Scotland) arrives at Holyrood, it is entirely up to Holyrood to decide how it is spent. So for example, if spending on education goes up in England, there is no obligation on Holyrood to spend an additional proportionate amount on education in Scotland; how Barnett consequentials are spent is at the discretion of Holyrood. As Wilson states:

“The decision to give £500m less to local authorities while Scotland’s block grant increased by £250m (with an underspend of £350m from last year) was taken entirely in Scotland. The decisions to allocate Barnett consequentials so that NHS expenditure in Scotland has risen by less than in Tory England are taken entirely in Scotland.”

It is therefore disingenuous to claim that the root of all of Scotland’s problems lay with Westminster and the “austerity agenda”, for it is the Scottish Government led by the SNP that has the money and tools (with more to come) at its disposal to help improve people’s lives and prospects in Scotland. What matters is how it uses those tools.

On this point, Naomi Eisenstadt, its own independent adviser on poverty and inequality has reported that two of its landmark policies – the council tax freeze and free universal services – are not helpful for those in poverty and hardship. On the former, she said that it at a cost to councils and “with disagreements about the equality and poverty impacts of the freeze” – noting that “those on low incomes at or above the poverty threshold…may not be covered by [the] full council tax reduction.” On the latter, she warned that free universal services may lead to “spreading a limited budget too thinly to help those who need the service the most.”

In other words, these are Holyrood (not Westminster) policies that disproportionately benefit the well-off while those in poverty suffer from cutbacks either resulting from the provisioning of free services to people who can afford to pay or cash-strapped councils trying to adhere to the council tax freeze (under the pain of a financial penalty from the Scottish Government). She suggested shifting away from universalism to targeted provision of services that can be “delivered without stigma” and said that the government “should consider ending the council tax freeze from 2017/18 onwards.”

This assessment was not surprising to many people – particularly in the Labour Party like Wilson – who have been making these points for some time as a means to bring the SNP to task for the claims that it is progressive party standing for social justice, when its actions in government are at the least more centrist than its rhetoric.

For that matter, when it comes to government, choices have to be made. The SNP has chosen to fund the council tax freeze over allowing rates to rise on the better-off, and it has chosen to fund universal services (such as tuition-free universities) as opposed to spending money on those who need it most. When it comes to spending priorities with precious resources, the SNP has made its budgetary priorities known.

The problem according to Wilson, is not one of persecution, as it is one of distribution and priorities, and that Holyrood only needs to engage in “modest tweaking” to reduce inequality, such as raising taxes a bit and revamping government toward helping those who are disadvantaged. This is bolstered by a report from Scotland in Union, which surveyed economic experts and think tanks from across Europe who concluded that with its current powers and powers yet to come, Holyrood “now holds most of the powers it needs to promote economic growth, jobs and prosperity in Scotland.”

Instead, the SNP relies on the pitiful narrative about Scotland being the helpless, defenseless victim of the Union - always being flogged senseless and mercilessly by Westminster and belonging to a hopeless constitutional structure that does not work for Scotland and the Scottish people.

But again, if the SNP is all about refusing to accept a new fiscal settlement on the grounds that it is unfair, then what does it say about the current one? It reveals that – far from being hard-up – Scotland does well as part of the United Kingdom under the current system. With smart decisions, it can do even better under the new arraignments, as opposed to the constant complaints over perceived and hyped-up grievances and the well-worn Nationalist adage that “only with independence…” can Scotland fulfill its potential.

Even people who support separation acknowledge that going forward – having failed to break up the UK in 2014 – the goal is for a better Scotland. This was expressed by David Carr on Common Space when he asked: “Should we not simply be making Scotland a better place - for the hell of it?” To this end, he further said that “not everything…has to be about indy” and that Holyrood ought to use the powers it currently has (and is anticipated to have), because after all, not everyone supports separation – including many SNP voters.

He didn’t exactly say it, but he seemed to imply that if this is possible within the Union (which I believe has been the case), then so be it.

Meanwhile, The National stated in an editorial this week that the “SNP have always pushed for more devolution at all costs and have never shied away from that position” in the pursuit of independence, but now say that “Swinney and the government will have to ask if the powers promised in the Scotland Bill are worth whatever cost there may might be.”

This is quite an extraordinary statement from some of the same people who could not credibly answer the currency and other economic/financial issues two years ago, and appeared determined to go for separation at any cost. This cost will become more stark in a few months than it was then with the release of the latest Government Expenditures and Revenues Scotland (GERS), which are expected to reveal the impact of oil prices well below what the SNP’s White Paper projected for an independent Scotland (which would have become a reality in March this year had there been a vote for separation).

If the Nationalists cannot accept the cost of the promised powers – including the ability to set income tax and bands, keeping half of VAT revenues generated in Scotland, borrowing abilities, and new welfare powers – then how does this bode for accepting the cost of full fiscal autonomy or complete independence?

At this point, with all of the effort that has gone into the Scotland Bill and the negotiating the framework, it would be a shame to see it collapse at this juncture. Indeed, it is especially a shame considering that Swinney previously endorsed a method known as “indexed deduction”, which he hailed as “the most robust mechanism” for recalculating the block grant, and which has already been agreed to with regard to Holyrood’s existing income tax powers.

Either he got his figures wrong with “indexed deduction”, or he knows that with “per capita indexation”, he is offering an arrangement that the UK government cannot possibly sell the other nations of the UK and the UK as a whole. Their position has been that the Smith Agreement “was clear that Scotland should hold Scotland-specific risks, while the UK should hold UK-wide risks.”

If the SNP thinks that the “Scotland-specific risks” are too great, then perhaps they should admit it, and instead propose a UK-wide convention or a Royal commission to work out a new governmental and constitutional framework for the country and its constituent parts, so that all corners of the realm down the council level can have their say on what should happen going forward and come to an agreement that is fair to all.

Either that, or just keep Barnett the way it is. If anything, Swinney’s effort to “protect Scotland” financially shows how important the Union is to Scotland and that even the SNP is effectively conceding this reality.